Every organization today claims to follow a Secure SDLC.

- Security gates are in place. ✅

- Threat models are created. ✅

- Static and dynamic scanners run in pipelines. ✅

- Security teams sign off releases. ✅

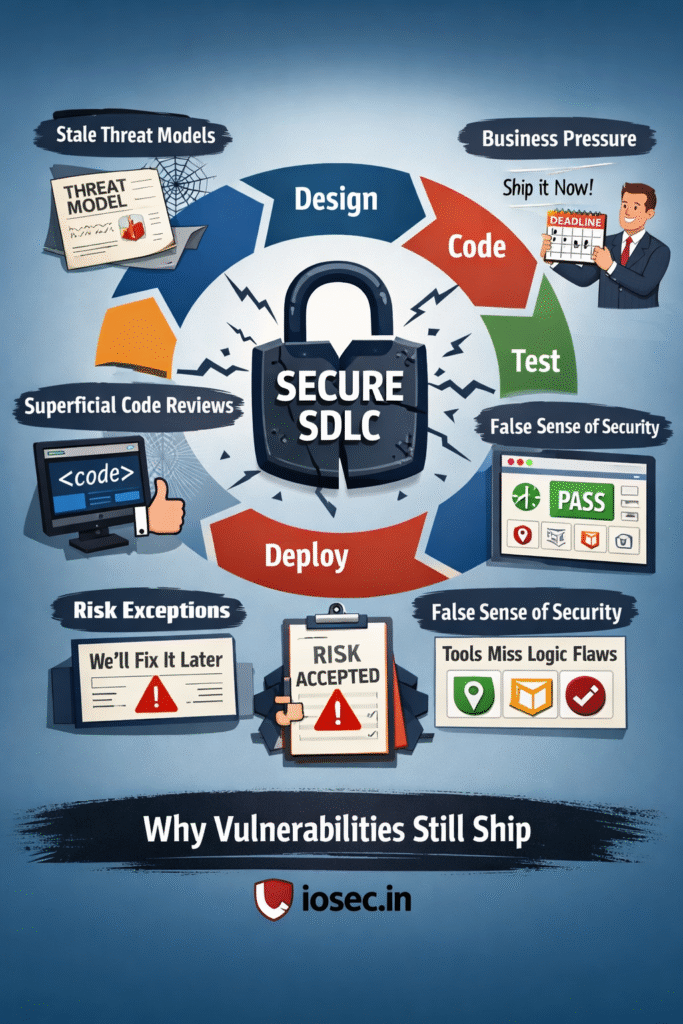

And yet, vulnerabilities still reach production — not rarely, but routinely.

Not exotic zero-days. Not nation-state exploits. But basic, structural flaws that should never have existed in the first place.

So the uncomfortable question is not whether Secure SDLC exists.

It’s whether it actually works the way we think it does.

The Reality Nobody Talks About

Secure SDLC is often presented as a neat, linear process:

Design → threat model → development → testing → release → monitor

But real-world engineering doesn’t work like that.

- Features change mid-sprint.

- Architectures evolve after deployment.

- Business priorities override technical concerns.

- Deadlines shift security from “mandatory” to “negotiable.”

Security doesn’t fail because teams ignore it.

It fails because reality slowly erodes the assumptions Secure SDLC was built on.

When Threat Modeling Comes Too Early — or Too Late

Threat modeling is often treated as a checkbox exercise.

In some organizations, it happens too early.

Architects design a system on whiteboards, assumptions are made about trust boundaries, data flows, and user roles. A threat model is documented, risks are categorized, and mitigation strategies are proposed.

Then development begins.

Over time, the system changes. New APIs are added. Microservices proliferate. A feature originally intended for internal use is exposed to external clients. Authentication logic is refactored. Third-party integrations creep in.

But the threat model remains frozen in its original form — a snapshot of a system that no longer exists.

In other organizations, threat modeling happens too late.

By the time security teams are invited to review the architecture, the system is already built, contracts are signed, and go-live dates are locked. The threat model becomes less about identifying risks and more about justifying why those risks cannot be fixed in time.

In both cases, threat modeling becomes symbolic rather than operational.

Attackers, of course, don’t care when your threat model was created.

They care about how your system behaves today.

The Silent Power of Business Pressure

No Secure SDLC document mentions this explicitly, but everyone in engineering knows it:

The strongest force in software development is not technology — it is business urgency.

- A release is tied to a marketing campaign.

- A feature is promised to a key client.

- A competitor has launched something similar.

- Revenue projections depend on shipping before a certain date.

When security raises concerns at this stage, the conversation subtly changes.

It’s no longer: “Is this secure?”

It becomes: “Can we accept this risk for now?”

Risk exceptions start to appear.

On paper, they look controlled and temporary.

In reality, they often become permanent.

The vulnerability is documented, acknowledged, and consciously shipped.

Secure SDLC didn’t fail here.

It was overridden.

When Risk Exceptions Become the Norm

Risk acceptance is supposed to be rare and justified.

But in many organizations, it becomes a structural part of delivery.

Security teams identify an authorization flaw.

Developers agree it’s real.

Fixing it requires architectural changes.

Product owners ask a different question:

“Can we ship and fix it later?”

Later rarely comes.

Over time, organizations accumulate what can only be described as security debt — not because they don’t know what’s wrong, but because fixing it is always less urgent than shipping something new.

Secure SDLC was designed to prevent vulnerabilities from entering production.

Risk exceptions are the mechanism through which vulnerabilities are consciously allowed in.

Code Reviews That Miss What Actually Matters

Code reviews are often portrayed as a cornerstone of Secure SDLC.

But in practice, they tend to focus on what is easy to see, not what is dangerous.

Reviewers catch formatting issues, minor bugs, and obvious anti-patterns. They rarely catch subtle authorization flaws or business logic inconsistencies, because those require understanding not just the code, but the intent of the system.

A piece of code can be perfectly written and still be fundamentally insecure.

The problem is not the syntax.

The problem is the assumption behind the logic.

Secure SDLC often teaches developers how to write secure code, but not how to question insecure design decisions.

Security Tools and the Comfort of Green Dashboards

Modern pipelines are full of security tools.

SAST finds vulnerabilities in source code.

DAST scans running applications.

SCA detects vulnerable dependencies.

Container scanners flag misconfigurations.

When all dashboards turn green, organizations feel safe.

But most real-world vulnerabilities are not pattern-based.

They are logic-based.

No scanner will tell you that a user can approve their own transactions.

No tool will flag that an internal API has become externally reachable.

Automated checks will not understand that two individually safe features, when combined, create an exploit path.

Secure SDLC tools are excellent at detecting known problems.

Attackers specialize in exploiting unknown interactions.

The Timing Problem: Security Always Arrives at the Worst Moment

Security reviews often happen when they are least welcome.

- When a feature is already built.

- Deadlines are close.

- When teams are exhausted.

At that point, security findings feel like obstacles, not safeguards.

Developers don’t argue that security is unimportant.

They argue that it is impractical.

And they are often right — not because security is wrong, but because it was introduced too late to be integrated naturally.

Secure SDLC assumes security is continuous.

Reality often treats it as a late-stage interruption.

Secure Coding vs Secure Systems

One of the biggest misconceptions in cybersecurity is this:

If developers follow secure coding practices, the system will be secure.

This is rarely true.

Developers can use parameterized queries, validate input, encrypt data, and still build systems that are fundamentally insecure.

Because security is not just about how code is written.

It is about how trust is distributed.

When tokens are over-privileged, when services trust each other implicitly, when authorization logic is centralized in fragile components, vulnerabilities emerge not from bad code, but from flawed assumptions.

Secure SDLC often focuses on code quality.

Attackers exploit architectural blind spots.

The Truth About Why Vulnerabilities Still Ship

Vulnerabilities persist not because Secure SDLC is missing.

They persist because Secure SDLC is often treated as a framework to comply with, not a mindset to internalize.

- Systems evolve faster than threat models.

- Business priorities override security concerns.

- Risk exceptions normalize insecurity.

- Tools create a false sense of completeness.

- Architecture drifts away from original assumptions.

Attackers don’t break Secure SDLC.

They simply wait for reality to outgrow it.

A More Honest Definition of Secure SDLC

Secure SDLC is not a checklist.

It is not a set of tools.

Not a document.

It is the continuous tension between shipping fast and shipping safely.

And as long as speed wins more often than safety,

vulnerabilities will continue to ship —

not because organizations don’t know better,

but because they consciously choose differently.

Closing Thought

Secure SDLC is not broken.

It is misunderstood.

Organizations believe they are building secure systems because they follow secure processes.

Attackers know that processes don’t defend systems — people and decisions do.

Until Secure SDLC becomes less about compliance and more about courage,

the myth of “secure by design” will remain exactly that — a myth.